4 Preparedness

4 Preparedness

4.1 Preparedness arrangements

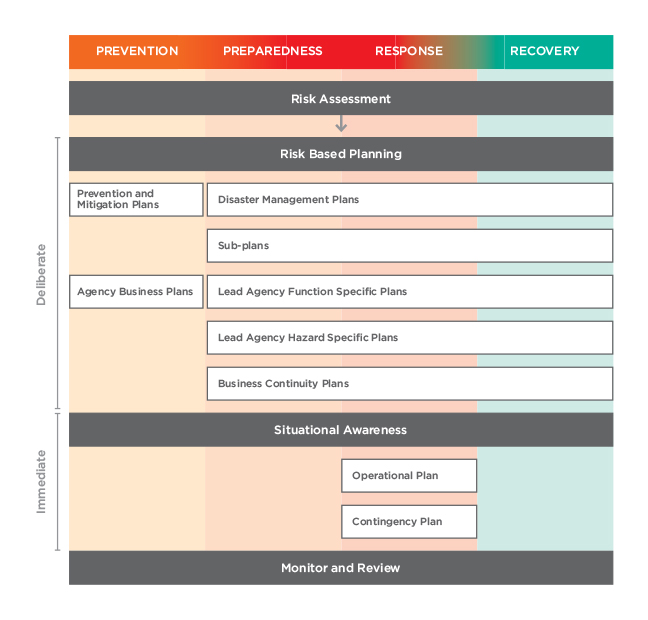

Coordinated action is essential when preparing for a disaster. This includes the development of plans or arrangements based on risk assessments and spans the full spectrum of disaster management phases: prevention, preparedness, response and recovery.

Local governments, disaster districts and the state prepare for disasters through a continuous cycle of risk management, planning, coordinating, training, equipping, exercising, evaluating and taking corrective action to ensure the effective coordination and response during disasters. Planning must occur both as core business and during disaster events.

Effective disaster management planning for all hazards is a key element of being prepared. Disaster management planning establishes community networks and arrangements to reduce risks related to disaster preparation, response and recovery. Disaster management plans allow all disaster management stakeholders to understand their roles, responsibilities, capability and capacity when responding to an event.

Key considerations for disaster management planning are detailed in this chapter to ensure:

- understanding of hazard exposures, vulnerabilities and triggers

- community awareness, education, engagement, information and warnings

- collaboration

- information sharing

- interoperability and capability development.

Figure 4.1 The above figure illustrates the comprehensive disaster management planning approach

4.2 Plans within the disaster management environment

4.2.1 State Disaster Management Plan

The SDMP describes Queensland’s disaster management arrangements, through which the guiding principles and objectives of the Act and the Standard are implemented.

All disaster events in Queensland, whether natural or caused by human acts, should be managed in accordance with the SDMP. The plan is consistent with the Standard and this Guideline as per section 50 of the Act and is supported by supplementary hazard-specific plans and functional plans.

The Queensland Recovery Plan is a Sub-plan to the SDMP.

L.1.004 State Disaster Management Plan 2017

L.1.261 Queensland Recovery Plan

4.2.2 Emergency Management Sector Adaption Plan for climate change

The EM-SAP is a high-level plan to support the sector in managing the risks associated with a changing climate and is the foundation for further collaborative implementation planning with the sector.

Aligned with the principles of the Queensland Climate Adaptation Strategy (Q-CAS), the EM-SAP provides guidance and support to the sector in understanding climate risks and planning for adaptation.

Toolkit

- Queensland Climate Adaptation Strategy (Q-CAS)

- Emergency Management Sector Adaptation Plan (EM-SAP) for climate change

- The science of climate change

- Why is climate change important to the sector

- Sector examples of climate adaptation – case studies

Consistent with the principles of the Q-CAS, adaptation should address the comprehensive approach to disaster management - prevention, preparedness, response and recovery, be adaptive to local conditions and the community and address acute major events and continuous incremental change. The EM-SAP actions that can be incorporated into preparedness, response and recovery are outlined in the table below.

Table 1. EM-SAP priorities and identified actions across preparedness, response and recovery.

| Priority # | Identified Actions | Preparedness | Response | Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Priority 1: Sector led awareness and engagement about climate change

| Build on existing community education and engagement programs within and outside the sector to include climate change science and associated impacts and create engagement and awareness where they don’t exist. | ☑ | ||

Incorporate or provide access to climate change education and training for the emergency management workforce. | ☑ | |||

Partner with schools, tertiary institutions and professional peak bodies to incorporate climate adaptation and emergency management as a consistent theme in curriculum and professional development training and education programs. | ☑ |

|

| |

Priority 2: Integration of climate change into sector governance and policy | Implement clear and long-term policy on climate adaptation within sector organisations. | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

Facilitate integrated planning across the sector and within government for the management of climate change and adaptation activities. | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | |

Influence legislative reform that supports a consistent approach to climate change at all levels of government. | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Examine sector procurement policy to understand future sustainability and adaptability to climate change, and where possible, to drive appropriate change in supply chains. | ☑ | |||

Priority 3: Enhancing the sector‘s understanding of climate change risk and its ability to adapt | Incorporate climate change consideration into organisational resilience practices, including enterprise risk management, business continuity planning, crisis management, emergency management and security management. | ☑ | ||

Develop an approach consistent with the ‘State Government pathway’ that enables a consistent evaluation of climate risk across sector organisations. | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | |

Work with local governments, disaster management groups and natural resource management groups to manage ‘natural infrastructure’ to reduce harm from natural disaster events. | ☑ | |||

Deliver the necessary data, tools and information to disaster management groups about climate change. | ☑ | |||

| Examine the feasibility of a review that assesses existing and planned sector facilities and their interdependencies against future climate change projections, with the aim of reducing future climate risk. | ☑ | |||

Priority 4: Research and development of new of new knowledge and supporting tools | Provide support and partnerships for research projects that inform sector climate adaptation, such as those that explore climate change science, application-ready data for activities such as risk assessment, and development of innovative adaptation solutions. | ☑ | ||

Provide access to data and decision support tools for understanding local-scale climate change risks. | ☑ | |||

Use advanced technology to support sector activities and decision-making in climate change applications, such as enhancement of personal protective equipment to cater for anticipated climate change, use of remote sensing and imagery, and evolving mitigation options. | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | |

Develop a dynamic suite of guidelines and tools that foster information sharing and provides examples of sector approaches or case studies of better practice for climate adaptation. | ☑ | |||

Priority 5: Allocation of resources to support sector adaptation | Influence funding stream alignment within and beyond the sector where possible to allow for climate adaptation initiatives. | ☑ | ||

Encourage sector organisations to allocate resources for research and development, risk assessment and planning and, capacity and capability enhancement for the purposes of climate adaptation. | ☑ | |||

Forge partnerships that foster investment in climate adaptation between and beyond sector stakeholders, particularly those that support cost-sharing or sharing of other resources. | ☑ | |||

Identify opportunities across all levels of government to enhance the coordination of resources targeting climate adaptation. | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | |

Priority 6: Increasing the resilience of infrastructure critical to the sector and community | Understand infrastructure interdependencies and vulnerability of the sector, and plan and implement adaptation solutions. | ☑ | ||

Influence the incorporation of climate scenarios into land-use planning for essential infrastructure and communities. | ☑ | |||

Foster partnerships and joint planning between the sector and infrastructure operators and owners. | ☑ | |||

| Where possible, ensure sector organisations are involved in land-use and infrastructure planning processes and are resourced to effectively contribute. | ☑ | |||

Priority 7: Promoting and enabling community resilience building and self-resilience | Continue to advocate for and facilitate activities that foster community resilience. | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

Influence land-use and urban planning through incorporation of climate change scenarios and risk information. | ☑ | |||

Undertake engagement activities that incorporate community self-reliance and resilience-building activities in preparation for, and use during, times of disaster. | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Work closely with other government and non- government organisations to increase the resilience of the community to climate change. | ☑ | |||

Priority 8: Volunteerism, volunteering and workforce management | Evaluate the impact of climate change on the availability of volunteers across the sector to continue to deliver goods and services across the state. | ☑ | ||

Incorporate climate change risks into volunteering and workforce strategies and planning across sector organisations, and in emergency management planning. | ☑ | |||

| Foster partnerships between sector organisations, the community and beyond to enhance collaboration and cross-utilisation of the existing and future volunteer and paid workforce. | ☑ |

4.2.3 District Disaster Management Plan

In accordance with section 53 of the Act, DDMGs must prepare a DDMP for disaster management in the disaster district. DDMPs detail the arrangements within the disaster district to provide whole of government planning and coordination capability to support local governments in disaster management.

A DDMP should consider the LDMPs in the district to ensure the potential hazards and risks relevant to that area are incorporated. The plan should outline steps to mitigate the potential risks as well as identify appropriate response and recovery strategies

4.2.4 Local Disaster Management Plan

In accordance with section 57 of the Act, local governments must prepare an LDMP for disaster management in their LGA.

The development of a LDMP should be based on a comprehensive, all hazards approach to disaster management which incorporates all aspects of PPRR and specific provisions under sections 57 and 58 of the Act. It should outline steps to mitigate the potential risks as well as identify appropriate response and recovery strategies.

4.2.5 Sub-plans

Sub-plans sit within the LDMPs or DDMPs. They address specific vulnerabilities to the area, identified during the risk assessment. Sub-plans could include:

- Communication plan

- Resupply plan

- Evacuation plan

- Transport plan

- Recovery plan.

4.2.6 Business Continuity Plan

Business continuity planning (BCP) enhances community resilience by ensuring disaster management stakeholders (government, NGOs and businesses) can continue their core business following any critical incident or disruption.

The process of BCP assists organisations to:

- stabilise disruptive effects to service delivery during events

- identify, prevent and manage risks

- adopt an all hazards approach

- expedite response and recovery if an incident or crisis occurs.

Groups are strongly encouraged to undertake BCP to form part of the LDMPs and DDMPs to ensure the group can continue to operate during a disaster event to provide coordination and emergency support to the local community.

4.2.7 Functional Plans

A functional plan is developed by lead agencies to address specific planning requirements attached to each function. Although the functional lead agency has primary responsibility, arrangements for the coordination of relevant organisations that play a supporting role are also to be outlined in these plans.

The lead agencies and their responsibilities are detailed in Appendix C of the SDMP.

4.2.8 Hazard specific plans

A hazard specific plan is developed by a state government agency with assigned lead responsibility to address a particular hazard under the SDMP. An example of a hazard specific plan is an emergency action plan for referable dams.

Local and district disaster groups should be aware of these hazard specific plans as it informs and assists in their planning.

The lead agencies and their responsibilities are detailed in Appendix C of the SDMP.

4.2.9 Operational Plans

An operational plan is a response plan which outlines a problem/concern/vulnerability and identifies the appropriate actions (what? who? how? when?) to address the situation. Groups are encouraged to prepare an operational plan which sits within the disaster management plan and is developed after conducting a risk assessment.

4.2.10 Contingency Plans

A contingency plan is developed to assist with managing a gap in capability to ensure services are maintained. Contingency planning can be undertaken as deliberate planning or immediate planning (discussed further in section 4.3) as it groups are encouraged to do this planning to address gaps on an as needs basis.

4.2.11 Education and engagement planning

Critical elements of effective disaster management include educating, raising awareness and engaging with the community to create collaboration, cooperation and understanding among all stakeholders.

Community programs focus on creating resilient communities that understand the risks of potential disasters, are well prepared financially, physically, socially and mentally to minimise impacts, recover quickly and emerge stronger than their pre-disaster state.

As part of their risk management process, LDMGs and DDMGs are encouraged to identify community education, awareness and engagement as treatments for mitigating risks and increasing resilience and transition these elements into an integrated and comprehensive community education and awareness program.

Communication planning involves identifying opportunities for consistent messaging, joint programs and commonalities, in conjunction with the relevant stakeholders such as neighbouring LDMGs, DDMGs, NGOs or state level initiatives which may be leveraged locally (e.g. the Get Ready Queensland program).

The Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience’s Guidelines for the Development of Community Education, Awareness and Engagement Programs provides an excellent overview of the six key principles of effective programs:

- ‘localise’ programs and activities where possible

- develop a program theory model for programs and activities that will provide a template for detailed planning and implementation, a ‘roadmap’ for evaluation and a permanent record of the thinking that occurred during program development

- develop a small suite of programs and/or activities that focus on achieving different intermediate steps (processes) along the pathway from ‘risk awareness’ to ‘preparedness’ (planning, physical preparation, psychological preparation) and that are integrated 4 Preparedness Queensland Prevention, Preparedness, Response and Recovery Disaster Management Guideline 35 into a general plan for enhancing natural hazard preparedness in a locality or region

- where appropriate, consider an integrated approach to planning, program development and research

- conduct and report frequent evaluations of programs and activities to continually enhance the evidence base for what works in particular contexts in community safety approaches

- seek to optimise the balance between ‘central’ policy positions, agency-operational requirements and specialist expertise on the one hand and community participation in planning, decision making, preparation and response activities on the other

4.3 Planning

Planning involves clearly identifying:

- the desired end state and the objectives to be achieved

- how the plan is to be executed

- the resources required.

Effective planning is essential for a community to successfully prepare for, respond to and subsequently recover from a disaster event. Risk assessments, risk based planning and resilience are closely integrated through the planning process.

Planning provides a means for addressing complex problems in a manageable way. The most effective plans are clear, concise and direct.

Good planning involves projecting forward to influence events before they occur rather than attempting to respond as events unfold. It actively avoids or mitigates issues before they arise by involving relevant stakeholders and creating shared partnerships during the development phase.

Planning falls into two broad categories: deliberate and immediate.

- Deliberate planning – ideally conducted after a process of analysis, with planning commencing with scoping and framing such as depicted within section 4.3.1 Planning process. Deliberate planning projects well into the future to influence events either before they occur or to prevent them from occurring and to also realise objectives towards specific goals. This type of planning is generally:

- Broad

- flexible

- scalable

- risk-based

In terms of Queensland’s disaster management planning, the level of detail required in a deliberate plan will depend on the complexity of the risks analysed within the QERMF risk assessment (which in turn is based on the analysis of hazards and events likely to happen in the relevant area).

Deliberate planning requires assumptions about the future based on history and projections, such as the effect of climate adaptation.

Deliberate planning addresses key risks by describing:

- purpose of the plan

- roles and responsibilities

- coordination of tasks

- priorities for the relevant area based on identified risks

- trigger and escalation points to enact sub-plans

- resources required

- communication, consultation and collaboration required

- timelines.

Local, District or State Disaster Management Plans and sub-plans are the outcome of deliberate planning processes.

A beneficial outcome of deliberate planning in disaster management is the identification of residual risk – the risk that remains unmanaged, even when effective risk reduction measures are in place. This engenders an informed planning process throughout all tiers of Queensland’s disaster management arrangements and ensures a more 4 Preparedness Queensland 36 Prevention, Preparedness, Response and Recovery Disaster Management Guideline effective response and allocation of resources in the event of a disaster

- Immediate planning – is event driven and based upon the development of situation awareness. Immediate planning will identify the most likely through to credible worst case scenarios by assessing actual or impending event characteristics and projecting the potential impacts and consequences (e.g. the path of a severe tropical cyclone is forecast to cross the Queensland coast in a particular location – pre-impact analysis using geospatial intelligence will inform the assessment of the situation and identify immediate planning requirements).

Immediate planning rests on close monitoring of an emerging situation with the focus on developing a timely response.

4.3.1 Planning process

The planning process enables agreements between individuals, agencies and community representatives to meet communities’ needs during disasters. The plan becomes an accessible record of the commitments made to perform certain actions and to allocate physical and human resources. The steps involved in planning are outlined below.

4.3.1.1 Scoping and Framing

Scoping and framing enables planners to clearly and simply articulate complex problems by documenting:

- the purpose or reason for planning

- a broad description of how the problem may be resolved

- the desired future or ‘end’ state, often articulated as “what does ‘right’ look like?”

Scoping produces a broad overview of the situation, the initial identification and estimation of risks and any specific environmental considerations. It is also referred to as the problem space.

Framing is most important when dealing with large, geographically dispersed events. In short, it is a method for focusing on specific issues within a larger problem space.

Undertaking a QERMF risk assessment directly informs the scoping and framing components of disaster planning for a particular locality or district.

The process ensures the clear identification of the context, hazards, exposures and vulnerabilities within the area being assessed. This informs the risks to be addressed through the development of plans, such as a Local Disaster Management Plan (LDMP).

A collaborative approach among stakeholders – not necessarily just members of LDMGs or DDMGs – during the scoping and framing stage greatly assists with addressing identified vulnerabilities. For example, local owners and operators of critical infrastructure and representatives of community groups and community leaders would be excellent sources of knowledge for planning.

4.3.1.2 Course of Action Development

Multiple courses of action or a single effective solution may be identified depending on time, risk and or resource constraints. A range of factors including the need for phases, sequencing and synchronisation may be required, particularly if the solution covers a significant geographical area, involves coordination of multiple stakeholders as well as acquisition or deployment of logistical support.

Courses of action should always be critically appraised for:

- feasibility

- effectiveness and efficiency

- acceptability

- timeliness and risk

The development of a course of action should consider:

- What needs to be done? What is or may be exposed, vulnerable and at highest risk? This drives priority of action.

- What can be done? (feasibility):

- Possible courses of action - what capability is available that will prevent or resolve the problem/s and what is the capacity of that capability?

- evaluate and select the preferred course/s of action - what is the best option after considering all circumstances (considering acceptability, timeliness and the risk in undertaking that action)

Developing a plan – a plan is created after selecting the best option and determining how it can be done in 4 Preparedness Queensland Prevention, Preparedness, Response and Recovery Disaster Management Guideline 37 the available time and space and resource availability (effectiveness and efficiency).

Approving the plan – once a plan is developed, it must be approved. The approval will depend on the level the plan was created (local or district) and will need to be shared with appropriate stakeholders through Queensland’s disaster management arrangements, so that support and resourcing requirements are known and enacted.

Enacting or executing the plan – once the plan has been approved by the relevant authorising person or group, the strategy or plan must be implemented.

M.1.137 Risk Based Planning Manual

H.1.102 Queensland Emergency Risk Management Framework – Risk Assessment Process Handbook

L.1.209 Vulnerable Sections of Society Report

L.1.208 People with vulnerabilities in disasters: A framework for an effective local response

4.3.2 Effective risk-based planning

For Queensland disaster management, risk-based planning occurs through the completion of a QERMF risk assessment. Key considerations for each step of the QERMF process are outlined below. In addition to these, planners also should include the following considerations:

- comprehensive approach (plan across PPRR)

- integrated approach – all agency

- all hazards focus

- locally led

4.3.2.1 Hazard Identification

The hazard analysis identifies most likely and credible worst case scenarios as well as hazards specific to the assessed area. This ensures a realistic and relevant approach tailored to the characteristics of the specific area. Hazard identification is achieved through evaluating relevant hazard data to the area being assessed

4.3.2.2 Identifying Stakeholder Groups

Inviting and uniting relevant stakeholders (including industry stakeholders and community representatives) to conduct both risk assessments and planning activities is imperative to creating successful strategies for responding to identified vulnerabilities. All levels of Queensland’s disaster management arrangements – local, district and state – should do this.

4.3.2.3 Risk Assessment

A risk assessment identifies vulnerabilities and the capability and capacity for managing them, evaluates the effectiveness of existing controls, and identifies gaps in systems, processes, plans or capability.

A risk assessment also assists in determining specific stakeholders’ capabilities and capacities to address identified vulnerabilities relating to their assets or responsibilities. This allows LDMGs and DDMGs to identify any gaps, delineate responsibilities between them and specific stakeholders, champion localised risk sharing arrangements and clearly articulate any residual risk requiring action.

4.3.2.4 Communicating Residual Risk

Communicating gaps in capability and capacity within Queensland’s disaster management arrangements, enables each level of the arrangements to plan appropriately in support of the identified risks.

For more information regarding the declaring of a disaster situation refer to Chapter 3 section 3.5.

4.3.2.5 Developing Plans

By adopting the risk-based planning approach in the QERMF, plans become fit-for-purpose and efficiently and effectively address the identified issues

4.3.2.6 Community Education

Effective plans identify community awareness and resilience programs as part of the risk assessment. This assists with informing further planning strategies such as community education programs relating to specific hazards or plans.

4.3.2.7 Training

Training is also a key component within the planning process, particularly for those with roles and responsibilities in enacting a specific plan.

For more information regarding the training refer to Chapter 2 section 2.2.

4.3.2.8 Exercise

The development and enactment of scenarios to evaluate the effectiveness of plans is key to good governance and assurance.

Analysing plan effectiveness – both in times of exercise and post-incident response – enhances planning outcomes and enables the implementation of lessons identified.

Accordingly, plans must be adjusted where necessary. Flexibility and agility in planning, rather than rigidity, ensures plans remain relevant, realistic and risk-based

L.1.272 Managing Exercises – Handbook 3

4.4 Planning Considerations

4.4.1 Activation and triggers

Timely activation, across all levels of Queensland's disaster management arrangements, is critical to an effective disaster response. Disaster management arrangements in Queensland are activated using an escalation model based on the four levels – Alert, Lean Forward, Stand Up and Stand Down. Disaster management groups' journey through this escalation phase is not necessarily sequential. Rather, it responds to the changing characteristics of the location and event.

Activation does not mean disaster management groups must be convened but that they must be kept informed about the risks associated with the potential, evolving disaster event.

RG.1.157 Disaster Management Group Activation Triggers Reference Guide

When planning for activations and triggers, consider the following:

- Activation and trigger procedures are informed by the risk assessment process based on the likelihood of potential hazards or disaster events affecting the local area.

- Activation procedures should be included in disaster management plans at all levels and it is recommended they articulate:

- agreed and documented levels of activation and escalation procedures that include trigger points and required actions during pre-emptive operations and Lean Forward and Stand Up phases

- established and documented responsibility to monitor the indicators of disasters, including ensuring timely activation is achieved.

- Ensure training, as appropriate to the role or function as outlined in the QDMTF, is undertaken by all members and other persons who hold responsibilities for situational awareness activities.

- Activation and trigger procedures are informed by the identification of risk, the likelihood and consequences of the risk, are appropriate to the purpose, role and function of the entity in question and then timed and nuanced to meet the needs of relevant communities.

4.4.2 Disaster Coordination Centres

Disaster coordination centres bring together organisations to ensure effective disaster management before, during and after an event. The primary functions of disaster coordination centres revolve around three key activities:

- forward planning

- resource management

- information management.

Specifically, functions include:

- analysis of probable future requirements and forward planning including preliminary investigations to aid the response to potential requests for assistance

- implementation of operational decisions of the disaster coordinator

- advice of additional resources required for the local government to the DDMG

- coordination of allocated state and Australian government resources in support of local government response

- provision of prompt and relevant information across local, district and state levels concerning any disaster events.

For more information regarding the activation and operations of disaster coordination centres refer to Chapter 5, section 5.4.

When planning for disaster coordination centres, consider the following:

- Determine resource capacity and capability requirements and gaps based on risk, including any facilities, information, people, material, equipment and service needs necessary for the effective operation of the coordination centre during a disaster.

- Prior to an event, undertake analysis of disruption related risk and a business impact assessment (BIA) to establish, agree to and document BCP arrangements for the centre.

- Referring to the risk assessment and BIA prior to an event:

- identify and ensure arrangements are in place for appropriate resource capability and capacity to effectively operate the coordination centre

- establish, agree to and document resource capability requirements to confirm the skills and knowledge required for roles within the disaster management group training program, aligned to and informed by the QDMTF

- establish, agree to and document sound financial management and accountability processes and procedures to be followed in the centre

- establish, agree to and document state government agencies' and disaster management groups' roles and responsibilities within the coordination centre, across all phases and at all levels of activation within the SDMP and disaster management sub-plans

- establish, agree to and document state government agencies' and disaster management groups' processes and standard operating procedures which guide the coordination of disaster operations and activities within the coordination centre, across all phases and at all levels of activation within the SDMP and disaster management sub-plans

- agree to a system or process for managing the resources required to staff the coordination centre (e.g. surge capacity, staff rostering/rotation and fatigue considerations) to ensure resource capacity limits of the disaster coordination centre are known and communicated to relevant groups

- ensure a system or procedure for receiving and distributing information between disaster management groups and entities for coordinating and sharing information (such as decision making, tasking, communications and requests) across all phases and at all levels

- ensure Agency Liaison Officers' core business processes and procedures include the support of disaster operations within disaster coordination centres to maintain effective and efficient delivery of responsibilities (such as functional lead agency responsibilities described in the SDMP)

- ensure arrangements are established for the deployment, reception, registration, briefing, tasking, coordination, supervision and debriefing of coordination centre staff deployed to support resource capacity and capability

- identify an approach for communicating with coordination centre resources, including a communication plan which includes information for the individuals and organisations who play a role within the coordination centre (e.g. disaster management plan, risk assessment, processes or procedures)

- ensure training, as appropriate to the role or function as outlined in the QDMTF, is undertaken by all identified people and LDMG members who hold responsibilities within the disaster coordination centre.

- Activate the centre in line with documented processes and procedures for activation triggers documented within the disaster management plan.

- Undertake immediate planning to enact the relevant plan, procedures and processes for response.

- Consider maintaining the use of coordination centre staff until full transition to recovery is achieved.

- Identify a process where the efforts of coordination centre staff are recorded, acknowledged and communicated.

- Review the engagement and management of coordination centre staff to identify lessons identified and development needs to build greater resilience in future.

4.4.2.1 Local Disaster Coordination Centres

LDCCs are either permanent or temporary facilities within each LGA, or combine LGA, established to support the LDMG during disasters.

LDCCs operationalise LDMG decisions, as well as plan and implement strategies and activities on behalf of the LDMG during disaster operations.

The main function of the LDCC is to coordinate resources and assistance in support of local agencies and stakeholders engaged in disaster operations.

4.4.2.2 District Disaster Coordination Centres

A DDCC is established to support the DDMG in the provision of state level support to affected local governments within that district.

The DDCC coordinates the collection and prompt dissemination of relevant information to and from LDCCs and the SDCC about disaster events occurring within their disaster district. The DDCC implements decisions of the DDC and DDMG and coordinates state and Australian Government resources in support of LDMGs and disaster affected communities in their district.

4.4.2.3 State Disaster Coordination Centre

The SDCC is a permanent facility located at the Emergency Services Complex at Kedron, Brisbane.

The SDCC operates as a 24/7 Watch Desk when not activated for a disaster, and is staffed and maintained in a state of operational readiness by QFES.

The SDCC supports the SDC by coordinating the state level operational response capability during disaster operations. The SDCC ensures that information is disseminated to all levels in Queensland’s disaster management arrangements, including the Australian Government.

4.4.3 Financial Arrangements

Disaster management groups must plan financial services to support frontline response operations and ensure the appropriate management of financial arrangements.

For more information regarding the financial planning refer to Chapter 5 section 5.9.

Each support agency is responsible for providing its own financial services and support to its response operations in the field. When planning financial management and expenditure, consider the following:

- Use the risk management process to first ascertain mitigation across all phases of operation and then identify funding requirements to enable those mitigation strategies.

- Identify and capture funding programs available to support the financial expenditure related to disaster operations and ensure the requirements for evidencing claims are built into financial management processes and procedures.

- Ensure local governments' and other responding agencies' internal financial management processes and procedures support a disaster event and enable eventual financial claiming process to recoup funds.

- Transition agency specific mitigation actions to agency business plans to ensure the appropriate resourcing and funding of their commitments across all phases of disaster management.

- Agree on, document and embed event-related financial management processes and procedures to ensure expenditure is appropriately endorsed, captured and claimed by agencies and groups from the onset of operations (e.g. the type and limit of expenditure permitted, relevant agency's procurement policy, requirements detailed in funding programs).

- Establish and document capability in the plan to monitor agreed financial management processes and procedures and ensure expenditure is appropriately endorsed, captured and claimed by agencies and groups from the onset of operations.

- Ensure agreed financial expenditure is appropriately endorsed and immediately captured by agencies and groups from the onset of disaster operations.

- Ensure agreed financial expenditure is claimed against the appropriate arrangements where applicable, such as the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA) or State Disaster Relief Arrangements (SDRA) if activated.

4.4.4 Predictive capabilities

A range of technical information is available to decision makers within the disaster management system. This information supports decision making, particularly during the response phase, and informs the development of public information and warnings. Spatial data, maps and web-based mapping applications are typically available at operational level in Councils and State Government Agencies. Other information available to decision makers includes predictive modelling for a range of hazards, in particular bushfire and flooding. This modelling assists decision makers by providing an indication of the direction and extent of the hazard that is or may impact an area. Where LDMGs do not have access to locally produced modelling products, this information is available from the State Disaster Coordination Centre to disaster management groups via the request for assistance process.

The technical information provided through these applications enables the development of public information and warnings. For example, all current public warnings in relation to bushfire are available through the Queensland Fire and Emergency Services website.

These warnings are visually represented through the overlay of polygons on current risk areas and include warning types and action statements in accordance with the Australian Warning System (AWS).

4.4.5 Communications and systems for public information and warnings

All disaster management groups play an important role in notifying and disseminating information to members of their respective groups and the wider community.

The agency responsible for issuing official warnings depends on the hazard. For example, QFES is responsible for issuing bushfire warnings, the BoM is responsible for issuing cyclone, storm and flood warnings and Queensland Health is responsible for issuing warnings about public health and heatwave health. These agencies are also to ensure the warnings are provided to other relevant response agencies and for ensuring the community is aware of the meaning of the warnings and their accompanying safety messages.

Each disaster management group should have an established notification and dissemination process prepared, documented within its plan and able to be implemented, which considers and addresses the time restrictions of rapid onset events like severe weather events.

Groups should also ensure the effective collection, monitoring, management and dissemination of accurate, useful and timely information and warnings to the public prior to, during and after disaster events to:

- educate and inform relevant stakeholders and community members of disaster management information, warning methods and products

- inform the relevant stakeholders and community members of an impending or current hazard

- promote appropriate prevention, preparedness, response and recovery actions.

The process of disseminating information and warnings does not depend on the activation of a disaster management group. Rather, it is the standard responsibility of disaster management groups.

L.1.161 Emergency Warnings: Choosing Your Words

4.4.5.1 Local Communications

Local governments may use local early warning systems and communication channels to issue information to provide advance warning of severe weather or other public safety events to help prepare and protect people and property.

Early warning systems are opt-in systems providing information and warnings on registered or physical locations.

Providing timely and accurate information about an imminent hazard gives people the opportunity to prepare by taking action to reduce the level of risk for themselves and others. Further, the ability to communicate directly with communities – and therefore keep them informed – increases their resilience. When planning for local communication channels, consider the following:

- Identify a scale of notification and suitable communication channels to ensure accurate, reliable, relevant and timely information is provided to people, groups and communities as required.

- Identify the most effective communication channels available to reach stakeholders and community members in selected areas (e.g. SMS on mobiles, email, landline, fax, web, social media, broadcast media).

- Determine the most appropriate communication channels based on the characteristics of the population (e.g. size, structure, distribution, age) to ensure appropriate methods are used.

- Identify the capacity and capability needed to manage the processes for local information provision.

- To assist in the delivery of information, groups may consider:

- resourcing requirements outside of group activations and disaster events

- using interpreter services

- using community engagement experts.

- Use 'opt-in' early warning services and systems to provide location based severe weather and incident advice.

- Assess the effectiveness of communication channels to ensure they are appropriate for the needs of the area (e.g. a system used in South-East Queensland may not be suitable for Far Northern Queensland due to remote communities with limited reception and/or internet access).

- Agree on and document in the disaster management plan, roles, responsibilities and processes for using various communication channels.

- Ensure training, as appropriate to the role or function as outlined in the QDMTF, is undertaken by all identified people and LDMG members who hold responsibilities for local notification systems.

- Identify, agree on and document in the disaster management plan, alternative processes where 'opt-in' early warning services and systems are not suitable.

- Exercise information and warning procedures, including testing community understanding of content, perception of authority and response.

- Capture the lessons identified from exercises to ensure the continuous improvement of the plan, the system and the messages to ultimately increase community resilience.

- Consider the distribution of information and warnings to communicate actions to be taken during prevention, preparedness, response and recovery phases.

- Ensure communication requirements are informed by the identification of risk, the likelihood and consequences of that risk, appropriately timed and nuanced to achieve the purpose of that communication and to meet the needs of the targeted audience.

- Monitor and review information and warning processes to include lessons identified from events and ensure continuous improvement to increase community resilience.

4.4.5.2 Standard Emergency Warning Systems

In 1999, all Australian states and territories agreed a Standard Emergency Warning Signal (SEWS) would be used to assist in the delivery of public warnings and messages for major emergency events.

SEWS is a wailing siren sound used as an alert signal to be played on public media to draw attention to the emergency warning. The signal is sounded immediately before the emergency warning message in potentially affected areas.

Responsibility for the management of SEWS in Queensland rests with the QFES Commissioner in coordination with the Queensland State Manager BoM for meteorological purposes.

When planning for the use of SEWS, consider community education, awareness and engagement programs to ensure the importance of SEWS is understood, including actions to be undertaken, by the wider community.

M.1.171 The Standard Emergency Warning Signal Manual

4.4.5.3 Emergency Alert

EA is a national telephone warning system used to send voice messages to landlines and text messages to mobile phones within a defined area about likely or actual emergencies. EA provides a non-opt out capability to maximise coverage.

The management and administration of EA in Queensland is the responsibility of QFES, however other agencies can request the use of the system. EA is used as one element in a suite of channels for providing community information and issuing warnings.

The use of EA is guided by applying the EA decision-making criteria (provided in the toolkit) to emerging events to ensure that appropriate, accurate, timely and relevant community safety messages relating to a major imminent emergency or disaster are urgently distributed to those who need to receive them.

For more information regarding Emergency Alert and additional community safety information refer to the Emergency Alert website.

When planning for the use of EA, consider the following:

- Undertake an analysis of identified risks which may require an Emergency Alert campaign based on the likelihood of potential hazards or disaster operations affecting the local area.

- Identify, agree to and document the process, roles and responsibilities for the authorised use of EA within the disaster management plan.

- Develop pre-prepared polygons and messages to be stored on the QFES EA Portal, based on the risk assessment process, which will prompt appropriate community response and action. The message must be:

- simple, interesting and brief

- suited to the needs of the community

- worded in accordance with advice from the relevant lead agencies

- used in the appropriate templates.

- Identify, agree to and document opportunities for a collaborative approach with relevant stakeholders. As an example, in locations where hazards and community characteristics are similar across multiple LGAs, the relevant LDMGs in conjunction with their DDMG/s should develop a centralised, joint strategy for information dissemination and evacuation direction routes.

- Establish and document responsibility for situational awareness in the disaster management plan to ensure the correct monitoring of key indicators, timely decision making and appropriate escalation procedures.

- Consider the likely community behaviour and perceptions, and operational requirements once an EA campaign has started, particularly the time and resources required for authorities to establish activities on which the community will rely. For example, if people are requested to self-evacuate, where should they go and what facilities and resources will be required when they arrive.

- Incorporate the use of EA into community education, awareness and engagement programs, and communication plans well before any event to ensure all stakeholders, including the wider community, understand the importance of the message and that subsequent action may be required.

- Exercise EA processes, including testing the community's understanding of content, perception of authority and response.

- Capture the lessons identified from exercises to ensure the continuous improvement of the plan, the system and the messages to ultimately increase community resilience.

- Ensure communication requirements are informed by the identification of risk, the likelihood and consequences of that risk, appropriately timed and nuanced to achieve the purpose of that communication and to meet the needs of the targeted audience.

- Undertake immediate planning to enact the relevant plan, procedures and processes for response (e.g. Evacuation Sub-plan, Public Information and Warnings Sub-plan).

- Align communication requirements with the recovery operations affecting the local area.

- Capture the lessons identified from exercises to ensure the continuous improvement of the plan, the system and the messages to ultimately increase community resilience.

M.1.174 Emergency Alert Manual

RG.1.273 Emergency Alert Incident Controller Check List

RG.1.178 Emergency Alert: Authorising Officer Check List

D.1.176 Emergency Alert: Process Map

F.1.177 Emergency Alert: Request Form (PDF)

F.1.177 Emergency Alert: Request Form (WORD)

4.4.5.4 Tsunami Notifications

The BoM developed and issued the Queensland Tsunami Notification Protocol in 2009. The Joint Australian Tsunami Warning Centre (JATWC), operated by BoM and Geoscience Australia, issues warnings for tsunamis in Australia. Tsunami bulletins, watches, warnings, cancellations and event summaries are part of a suite of warnings for severe weather events and hazards issued by the BoM.

The JATWC notifies the BoM's Queensland regional office by telephone before issuing a tsunami warning and, in turn, the BoM's Queensland regional office confirms receipt of the warning by the SDCC by telephone.

Those who receive the message, at all levels of Queensland's disaster management arrangements, should ensure the community is aware of the meaning of the warning notification and accompanying safety message.

For more information regarding weather warning information refer to the BoM website

M.1.183 Queensland Tsunami Notification Manual

D.1.184 Queensland Tsunami Notification Responsibilities Diagram

When planning for tsunami notifications, consider the following:

- Undertake analysis of identified exposure to elements within the community which may be vulnerable to a tsunami, based on the likelihood of the potential hazard affecting the local area.

- Identify, agree to and document processes, roles and responsibilities for distributing warning messages via multiple mediums, taking into account complementary existing tsunami warning systems operated by other agencies (e.g. tsunami warning systems from BoM and the SDCC, the use of EA, media and local warning systems).

- Identify, agree to and document within a communications plan the most appropriate channels for providing timely information to stakeholders and community members. This includes pre-scripted messages based on established JATWC messages to be delivered by local leaders (usually the Mayor or other designated LDMG representative).

- In conjunction with state government agencies and relevant disaster management groups, ensure processes and standard operating procedures which guide the coordination of the tsunami warning are seamless and consistent. Provide key contacts within LGAs to be advised by the state government agencies in the event of a tsunami warning.

- Consider the likely community behaviour and perceptions, and operational requirements once a tsunami warning or EA campaign has started, particularly the time and resources required for authorities to establish activities on which the community will rely. For example, if people are requested to self-evacuate, where should they go and what facilities and resources will be required when they arrive?

- Document community education, awareness and engagement programs to ensure a broad understanding of tsunami warnings and actions to take on the receipt of warnings.

- Ensure details of recipients remain up-to-date and any changes are provided to the BoM and the SDCC, and other agencies with responsibilities for the transmission of warnings.

- Test the system at least annually.

- Ensure communication requirements are informed by the identification of risk, the likelihood and consequences of that risk, appropriately timed and nuanced to achieve the purpose of that communication and to meet the needs of the targeted audience.

4.4.5.5 Media Management

Each disaster management group is strongly encouraged to develop a media strategy as part of its disaster management plan that:

- is flexible for application in any given event (all hazards)

- identifies key messages to inform the community including:

- reinforcing the LDMG's role in coordinating support to the affected community

- reinforcing the DDMG's role in coordinating whole of government support to LDMGs (and the affected community)

- identifies preferred spokespersons for factual information (e.g. evacuation measures, road closures)

- is consistent with the Crisis Communication Network arrangements outlined in the Queensland Government Arrangements for Coordinating Public Information in a Crisis.

Arrangements regarding community awareness, public information and warnings including media management during disaster operations are to be considered for inclusion in LDMPs and DDMPs.

H.1.159 Queensland Government: arrangements for coordinating public information in a crisis

4.4.6 Evacuation and sheltering arrangements

Evacuation is a hazard mitigation strategy and a risk reduction activity that lessens the effects of a disaster on a community. It involves the movement of people to a safer location and their subsequent safe return. Evacuation planning is essential to ensure it is implemented as effectively as possible.

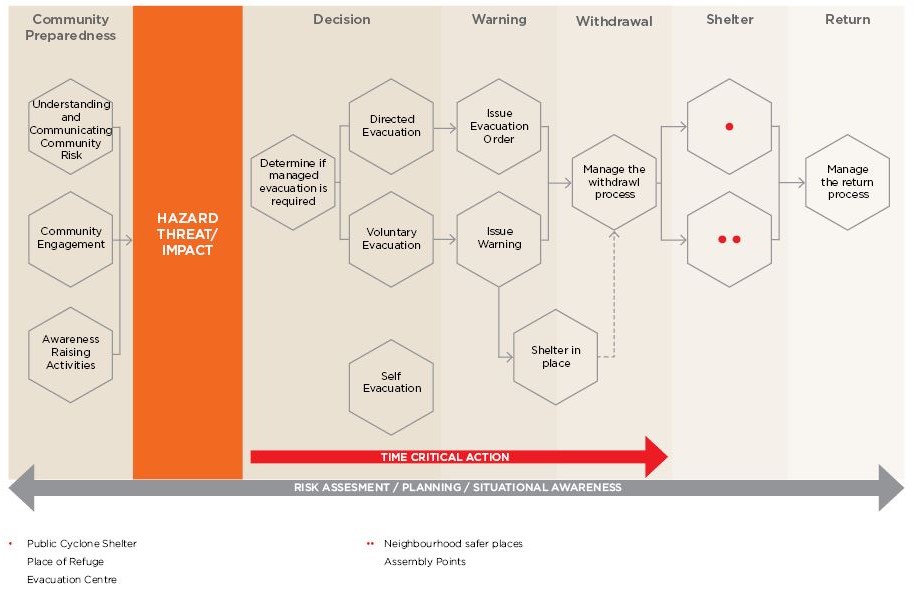

Evacuation may be undertaken in the following ways:

- Self-evacuation – this is the self-initiated movement of people to safer places prior to, or in the absence of, official advice or warnings to evacuate. Some people may choose to leave early even in the absence of a hazard but based on a forecast. Safer places may include sheltering with family or friends who may live in a safer building or location. Self evacuees manage their own withdrawal, including transportation arrangements. People are encouraged to evacuate early if they intend to evacuate.

- Voluntary evacuation – also known as recommended evacuation is where an evacuation advice has been issued, with people strongly encouraged to consider enacting their evacuation plans. Voluntary evacuees also manage their own withdrawal.

- Directed evacuation – also known as compulsory evacuation is where a relevant government agency has exercised a legislated power that requires people to evacuate. A directed evacuation under the Act requires the declaration of a disaster situation. A DDC may declare a disaster situation which requires the approval of the Minister for Fire and Emergency Services and must be made in accordance with section 65 of the Act. During a disaster situation, the DDC and Declared Disaster Officers are provided with additional powers under sections 77-78 of the Act. These powers may be required to give effect to a directed evacuation. A LDC, as part of the LDMG, may make a recommendation to a DDC that a directed evacuation is required, based on their situational awareness in preparation for an imminent disaster. However, as the LDMG/LDC has no legislative power to effect a directed evacuation, the responsibility for authorising a directed evacuation remains with the DDC. When an evacuation is directed, general advice and direction will be provided in relation to timings, places of shelter, location and preferred evacuation routes.

Wide ranging evacuation and direction powers are provided to the police under the Public Safety Preservation Act 1986, to control a declared situation.

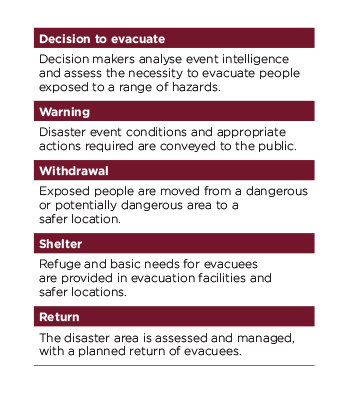

An evacuation involves five stages, shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 The five stages of an evacuation

Planning at each of these stages is crucial. Specific planning considerations are detailed further in this chapter.

Figure 4.3 illustrates the spectrum of the evacuation process. An evacuation is not considered to be complete until all five stages have been implemented.

Figure 4.3 The entire spectrum of the evacuation process demonstrates the need for planning at every stage.

International experience indicates mass evacuation can cause anxiety and stress and lead to panic and loss of life. It is for this reason that it is recommended plans be developed based on credible worst case scenario, taking into consideration the scale of the event through immediate planning. An evacuation well-planned and communicated prior to the occurrence of an event will minimise risks to both the community and disaster management personnel.

Evacuation facilities and safer locations describe a variety of sites and buildings which may need to be established to accommodate people during an evacuation. Categories of evacuation facilities comprise:

- Shelter in place – if evacuation is not directed, residents are encouraged to seek refuge in their own homes or with family who may live in a safer building or location.

- Evacuation centre – located beyond a hazard to provide temporary accommodation, food and water until it is safe for evacuees to return to their homes or alternative accommodation.

- Public cyclone shelter – a building designed, constructed and maintained in accordance with government requirements and provides protection to evacuees during a cyclone.

- Place of refuge – a building assessed as suitable to provide protection to evacuees during a cyclone, but is not a public cyclone shelter. These are typically opened when the capacities of other evacuation facilities have been exceeded.

- Neighbourhood safe places – buildings or open spaces where people may gather as a last resort to seek shelter from bushfire.

- Assembly points - a temporary designated location specifically selected as a point which is not anticipated to be adversely affected by the hazard.

Although not an evacuation facility, Recovery Hubs are established to provide a range of services to facilitate recovery including welfare, support, financial and emotional recovery services. Recovery Hubs are typically managed by the Department of Communities, Disability Services and Seniors. Planning should include options for locations for these hubs.

Disaster management groups plan and coordinate their evacuation procedures to ensure efficient movement of people from an unsafe or potentially unsafe location to a safer location and their eventual return home. When planning an evacuation, consider the following:

- Local governments, in close consultation with their LDMGs, should analyse the identified exposure to elements within the community which may trigger the requirement for evacuation, based on the likelihood of these potential hazards affecting the local area (e.g. tsunami, cyclone, bushfire).

- Determine the most appropriate evacuation requirements based on the characteristics of the population (e.g. size, structure, distribution, age) to ensure an appropriate method is used.

- Identify the capacity and capability needed to manage evacuation processes, including resourcing requirements (e.g. interpreter services).

- Local governments, in close consultation with the LDMGs, should conduct evacuation planning prior to the onset of an event using their local knowledge, experience, community understanding and existing community relationships.

- Involve all identified key local, district and state stakeholders in evacuation planning and clearly identify, agree to and document the processes and roles and responsibilities of those involved.

- Develop an Evacuation Sub-plan which addresses:

- Scale – planning should be geared to the consequences of the reasonable worst case scenario within the local area considering the scale from small to mass evacuation, with a firm understanding of the potential number of people involved.

- Type of evacuation facility – – the variety of buildings and sites to accommodate evacuees in response to a disaster event. There is a requirement to be clear on the types of evacuation facilities – detailed previously in section 4.4.5 – in the planning process.

- Stages – evacuation sub-plans should follow the five stages of evacuation, as discussed previously: decision to evacuate, warning, withdrawal, shelter and return.

- Time – evacuation may be required before a disaster event impacts as a defensive measure, or post-impact as a result of the aftermath of the event, such as loss of services or severe damage to building structures.

- Notice – depending on the nature of the event an evacuation may be immediate with little or no warning and limited preparation time or pre-warned allowing adequate time for preparation.

- Compulsion – some individuals within the community may decide to self-evacuate prior to any direction from authorities. When evacuation is encouraged by authorities it is undertaken as either voluntary evacuation where exposed persons are encouraged to commence evacuation voluntarily, or directed evacuation, where exposed persons are directed under legislative authority to evacuate an area exposed to the impact of a hazard.

As the LDMG/LDC has no legislative power to effect a directed evacuation, the responsibility for authorising a directed evacuation remains with the DDC.

M.1.190 Evacuation and Sheltering Arrangements Manual

L.1.191 Food Safety in Evacuation Centres

H.1.193 Queensland Evacuation Centre Planning Toolkit

H.1.259 Queensland Evacuation Centre Management Handbook

L.1.255 National Planning Principles for Animals in Disasters

M.1.188 Public Cyclone Shelter Manual

M.1.189 Tropical Cyclone Storm Tide Warning Response System Handbook

Places of Refuge: Cyclones – Guidance on the site selection of buildings

Technical Guidance Document – Assessment of buildings as a Place of Refuge for Cyclones

- Consider the likely community behaviour and perceptions, and operational requirements once the decision to evacuate has been made, particularly the time and resources required for authorities to establish activities on which the community will rely. For example, if people are requested to self-evacuate, where should they go and what facilities and resources will be required when they arrive?

- Incorporate evacuation requirements into community education, awareness and engagement programs, and communication plans well before any event to ensure all stakeholders, including the wider community, understand the actions they need to take (e.g. evacuation zones should be easy to understand, identified and planned prior to the onset of any event to ensure they are clear to residents, transient populations and anyone new to the community).

- Identify, agree to and document opportunities for consistent messaging and the joint delivery of programs in conjunction with relevant stakeholders. As an example, in locations where hazards and community characteristics are similar across multiple local government and media broadcast areas, the relevant LDMGs in conjunction with their DDMG/s could develop a centralised, joint strategy for information dissemination and evacuation routes.

- Agree to a process for managing the resources required for an evacuation to identify any capacity limits and ensure adequate support will be available (e.g. a DDMG should use information provided by an LDMG to inform its own planning process and where appropriate, inform the SDMG of any need for additional support).

- Identify, agree to and document, in consultation with the relevant DDMG, the requirements to activate elements of the Evacuation Sub-plan to receive evacuees from other LGAs or districts.

- Where there is a possibility that returning will not occur in the short term, the Recovery Sub-plan should include strategies for managing displaced people and enabling their return as soon as practicable.

- Develop and agree to a communication plan with all relevant stakeholders and support agencies to increase consistency, enhance community partnerships and minimise the potential for confusion and time delays during an event that requires evacuation.

- Capture the lessons identified from exercises to ensure the continuous improvement of the plan, the system and the messages to ultimately increase community resilience.

- Document and schedule exercising of the Evacuation Sub-plan including testing of the community's understanding of content, perception of authority and response.

- Evacuation requirements are informed by the identification of risk, the likelihood and consequences of that risk, appropriately timed and nuanced to achieve the purpose of the evacuation and to meet the needs of the targeted communities.

- Undertake immediate planning to enact the relevant plan, procedures and processes for response (e.g. Evacuation Sub-plan, Public Information and Warnings Sub-plan).

- Undertake immediate planning, in consultation with the relevant groups, to provide appropriate recovery services to facilitate immediate, short term and longer term temporary accommodation solutions for displaced community members and incoming relief and recovery workforce.

4.4.7 Logistics

Meeting the resource needs of a disaster affected community requires a systemic approach supported by a risk management process, business continuity plan and partnerships with key stakeholders – such as suppliers – during the planning phase.

The function of logistics during a disaster event is the detailed organisation, provision, movement and management of resources required in disaster operations, in other words 'having the right thing, at the right place, at the right time.'

Logistics activities can be broadly broken into three phases:

- before the event

- during the event

- after the event.

Disaster management groups are strongly encouraged to plan their logistics to effectively manage the receipt and delivery of the appropriate supplies within the disaster affected area, in good condition, in the quantities required, and at the places and times they are needed.

Common logistics categories in Queensland include:

- managing requests for assistance (including offers of assistance)

- emergency supply

- council to council arrangements

- resupply operations.

When planning logistics, consider:

- Use the risk assessment of identified hazard exposures to elements to identify the need for appropriate logistical support, based on the likelihood of the potential hazard affecting the local area, as well as community need.

- Identify the capacity and capability necessary to manage and coordinate the receipt and delivery of the appropriate supplies, including requests for material assistance as well as requested and resources which may arrive en-masse to the affected area (e.g. SES deployed resources or spontaneous volunteers).

- Identify, agree to and document processes, roles and responsibilities within a Logistics Sub-plan to manage the request, receipt and delivery of the appropriate resources, materials and supplies within the disaster affected area.

- It is recommended logistic sub-plans include arrangements for:

- Emergency supply – a local emergency supply register which may include aviation providers, bedding suppliers, construction contractors, chemical/cleaning specialists, food stocks/stores, general hardware, hire equipment, refrigeration/ice, transport providers, waste management and water suppliers).

- Resupply – procedures for the resupply of isolated communities, isolated rural properties and stranded persons, as well as ensuring retailers and the wider community are aware of their responsibilities for periods of isolation (e.g. stocking up on sufficient foods, medicines, water, fodder stockpiles, fuel) with the long term aim of increasing resilience.

- Offers of and requests for assistance – the ability to coordinate, support and facilitate those requests (e.g. the booking of travel and accommodation for volunteers).

- In conjunction with relevant state government agencies and disaster management groups, ensure processes and standard operating procedures for the logistics function are seamless and consistent.

- Logistics sub-plans should incorporate the latest NDRRA and SDRA advice to assist decision making for emergency supply and resupply funding eligibility.

- Local supplier contacts who can assist in providing goods and services available to the group should be provided to the DDMG.

- Departments and agencies that require materials or resources for disaster operations must identify the availability of those resources within their core business, document their own internal acquisition/supply processes and support resource capability, and use these before requesting support through Queensland's disaster management arrangements.

- Ensure training, as appropriate to the role or function as outlined in the QDMTF, is undertaken by all identified people and LDMG members who hold responsibilities within the disaster coordination centre.

- Document community education, awareness and engagement programs to promote the importance of individual and community responsibilities for planning for and preparing adequate resources for a disaster.

- Exercise logistics operations including testing of the community's understanding of their responsibility, perception of authority and response.

- Exercise lessons identified are captured to ensure continuous improvement of the plan, the system and robust, fit-for-purpose logistics arrangements are in place to support community need.

- Identify resource needs using an informed analysis of community needs.

RG.1.196 Request for Assistance Reference Guide

4.4.7.1 Emergency Supply

Emergency supply is the acquisition and management of emergency supplies and services in support of disaster operations. The emergency supply process is generally conducted through the existing Request for Assistance (RFA) process.

Successful emergency supply stems from a combination of effective disaster plans, current supplier registers and an understanding of process at all levels of Queensland's disaster management arrangements to expedite requests.

4.4.7.2 Resupply operations

The size and geographic diversity of Queensland, the dispersion of its communities and the nature of the potential hazards makes it probable that many communities will be temporarily isolated at times by the effects of those hazards.

No two resupply operations are identical and LDMGs are encouraged to document in their disaster management plan the specific requirements of the community and the logistical considerations in conducting resupply operations for their LGA.

Resupply operations are not intended to ensure retailers can continue to trade nor are they a substitute for individual and retailer preparation and preparedness. Resupply operations are expensive and logistically challenging and must be considered as a last resort.

There are three distinct types of resupply operations traditionally undertaken in Queensland:

- resupply of isolated communities

- isolated rural property resupply

- resupply of stranded persons.

4.4.7.3 Council to council arrangements

The Council to Council Support Program (C2C) responds to the needs of councils affected by natural disasters and acknowledges the desire of unaffected councils to support their colleagues during these events.

During a disaster event, local councils may seek assistance from other local councils to provide personnel or physical resources (e.g. machinery, signs, bedding, vector control teams).

The C2C program is a streamlined method for providing assistance from one local government group to another within Queensland's disaster management arrangements.

Local requests for C2C support are made through the RFA process to the DDC via the LDMG.

For more information regarding the RFA process refer to Chapter 5 section 5.8.

4.4.8 Offers of assistance

Following disaster events, the public – in Queensland, across Australia and on some occasions overseas – generously offers assistance to affected individuals and communities in the form of financial donations, volunteering, and goods and services.

These offers of assistance provide significant support to those affected by a disaster event and aids local businesses and the wider community to recover. It is highly beneficial to have a plan for offers of assistance prior to a disaster event to maximise the associated benefits.

Offers of assistance are categorised under one of the following:

- Financial donations – may be offered spontaneously or in response to an appeal and are used to provide immediate financial relief and assistance.

- Volunteers – individuals, groups or organisations that offer to assist a disaster affected community.

- Goods and services – solicited or unsolicited goods and services offered by members of the public, community, businesses, organisations and corporate entities to support individuals and communities following disaster events.

- Corporate donations may include money, volunteers and goods and services.

4.4.8.1 Financial donations

Financial donations may be offered spontaneously, or in response to an appeal. Early and consistent public messaging is crucial to ensure spontaneous donations are directed appropriately.

A disaster management group may choose to manage financial donations internally or outsource the responsibility to another entity. Either way, it must ensure there are sufficient resources to maintain proper governance processes.

It is beneficial to have identified and established the preferred arrangements regarding offers of assistance well before a disaster event occurs. When planning for financial donations, consider the following:

- Determine how financial donations are going to be managed, either within a government agency or disaster management group or outsourced to, for example, a NGO.

- Determine any resource capacity and capability gaps to ensure appropriate (e.g. legal, ethical) management of financial donations.

- Identify and document the chosen arrangements for managing financial donations.

- Ensure sufficient resources exist for the management of financial donations. This may include agreements with NGOs before the event.

- Undertake a review of previous management of financial donations and ensure any identified recommendations are incorporated in disaster management plans.

- Develop standard operating procedures for the management of financial donations (e.g. record keeping, receipts, communication, winding up funds, service level agreement requirements if outsourcing).

- Advise relevant stakeholders, including LDMGs and DDMGs, of the preferred approach for the management of financial donations.

- Monitor financial donation arrangements and processes.

- Implement or continue consistent public messaging using appropriate channels to make financial donations.

- Monitor the administration of donations and ensure the distribution of funds undertaken in a timely manner.

- Review the management of financial donations to identify possible improvements.

4.4.8.2 Volunteers

Community members are renowned for becoming first responders in a disaster event.

This is known as emergent community response and recovery or community mobilisation and usually consists of friends, families and neighbours volunteering to help themselves and others through their interpersonal relationships and their socioeconomic connections.

This scenario of 'people helping people' who know and trust each other does not require formal coordination processes. Accordingly, this guideline does not further consider the management of this cohort.

People involved in community mobilisation do require clear communication about the disaster event and support services available along with the rest of the community.

Community mobilisation aside, two primary types of volunteers offer their time and skills during an event:

- Trained volunteers – individuals formally affiliated with an emergency service organisation or NGO (e.g. QFES SES and Rural Fire Service, Salvation Army and service clubs) and act under their respective organisations' direction and authority.

- Spontaneous volunteers – individuals or groups who are not skilled or trained to perform specific roles in disasters and are often not affiliated with an emergency or community organisation but are motivated to help.

Volunteers are the responsibility of the organisation for which they volunteer.

Following a disaster, an influx of spontaneous volunteers may arrive unsolicited at the scene of a disaster or approach organisations they wish to help. Volunteers often want to assist immediately but may not be aware of, or try to work around, existing local disaster management arrangements. They may not be prepared (or insured) for the risks, conditions or environmental dangers.

Planning will greatly assist with the coordination of activities associated with engaging, recruiting, training, supervising and ensuring spontaneous volunteers are properly registered, insured, safe and provide the required support to the community in a way that builds community resilience.

When considering offers from spontaneous volunteers, it is essential to assess the human and social, cultural, economic and environmental impact this may have on local community recovery, resilience building, the administrative and logistical requirements, the costs associated with managing spontaneous volunteers and coordination of the offers. Further, it is imperative that volunteering organisations put affected people's needs first and ensure their activities do not harm or hinder.